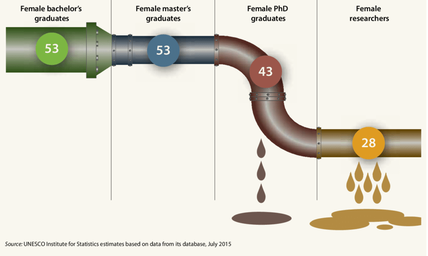

Figure 1. Figure 1. FIRST Robotics is home to a few initiatives focused on uplifting females pursuing STEM, most prominently being ‘FIRST #LikeAGirl’ and ‘LadiesFIRST. Programs like the ones just highlighted are imperative to allow women interested in STEM the support they require as their journeys past FIRST and highschool ensue. However, while idyllically apt– and an amazing look to the public–, how many of these programs can effectively alter long-time, homologous identity perceptors or historically binary societal ebbs and flows? Are women set up with the proverbial tools to succeed in these male-dominated fields, or are they unintentionally being set up to fail? In modern times, Sociologists have pondered a notion deemed the Leaky Pipeline Phenomenon, which explores the longevity of women pursuing STEM past their vocational years whether or not they are equipped with words of encouragement rather than strategy. The proportion of women in the STEM occupational fields has decreased continuously through the educational and vocational tracks, leading scholars to use the metaphor of a leaking pipeline. Women navigating through STEM-based career pathways drop out at higher rates along the way, as opposed to men going to school in the same field, resulting in a much smaller proportion of women at the end of the pipeline. A published paper by the Magazine of Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training emphasized the high dropout rate of female STEM students in college, attributing this as being a direct symptom of the aforementioned phenomenon. Women drop out due to various factors such as career mismatch, sex-based discouragement and identity-centered incongruence. Career mismatch, specifically, refers to the tendency of women to be overqualified for the careers that they end up in, likely due to their reluctance to enter jobs that are inconsistent with typical gender roles. That is, women who receive STEM degrees are not as likely to choose STEM careers– juxtaposed to males with comparable STEM degrees. As an additional result of career mismatch, this concept is symbolic of a positive feedback loop where women continue to serve jobs below their abilities, while their male counterparts reach higher leadership positions. This then amplifies the amount of women who feel a lack of self-confidence in their professional skills, a deficit in assertiveness on interactions with male counterparts, as well as a persistent pressure to assimilate to male culture. Look around– metaphorically, of course… When you see a woman in a higher position or even an unconventional role in engineering within FRC, let’s say… working in their team pit…, do you feel surprised, intrigued, or even merely recognize the implications of one taking a second to actively notice a feminine entity engaging in something traditionally done by masculine figures? Social role theory argues that societally shared beliefs on female or male ‘roles’ are preserved through “psychological processes that stabilize these societal practices by making them seem natural and inevitable to members of the society” (Markova, et. al., 2016). This is further evident when one looks at how only select women are championed for their work in male-dominated fields, and how ‘we’ would find it “out of place” to see a female with a yellow hard hat and a neon vest clocking into the construction site. Putting emphasis on women in STEM is of utmost importance, however, recognizing why much of society feels the need to apply this emphasis is even more integral. As, despite increasing numbers of women in science and engineering fields, this fact alone does not ensure any improved conditions for women’s real careers. Even women with a higher position in their respective fields have reported a lack of self-confidence to advocate for other, younger females within their departments. Thus, despite the increasing number of female students in gender-atypical study fields, “organizational structure within units, and the divisions they engender, continue to isolate women” (Markova, et. al., 2016). Despite the progress that is perceived at competitions, such as a female-operated Drive Team or female Programming and Mechanical Leads, there is still ample work to be done in the field of STEM to have these women appear as less of a show-stopper for being in leadership and more of a normalized construct within STEM fields. As notably theorized by West and Zimmerman, the scientists who constructed the idea of ‘doing gender’, “gender is not a set of traits, nor a variable, nor a role, but the product of social doings of some sort.” We, as a people, prescribe these social doings, meaning we also have the power to alter them and to dismantle them to an extent that lets each sex feel comfortable in the other’s historically-designated fields of work. Women should not have to ‘act like men’ in order to be assertive and assume leadership positions in STEM fields, nor should women have to go out of their way to advocate their worth. Women, as well as men, possess the innate abilities to lead or to serve, but, as a symptom of gender-roles, this autonomy has been somewhat stripped away from the sexes. But what can we do, even amongst FIRST Robotics members, to curve the narrative towards true acceptance over a figurehead status, and to patch up the leaky pipes? Firstly, companies and educational institutes need to hold themselves accountable, looking at their gender-based statistics or how they may have failed women as a symptom of their own ignorance. Companies should be challenged more to actively combat sexism and gender discrimination, effectively creating an inclusive working environment for young women in gender-atypical careers. Moving through this vein of thought, there are a few introductory tasks that may produce far more equitable working environments for women, beyond the current structure:

Citations:

Makarova, E., Aeschlimann, B. & Herzog, W. Why is the pipeline leaking? Experiences of young women in STEM vocational education and training and their adjustment strategies. Empirical Res Voc Ed Train 8, 2 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-016-0027-y “STEM Gender Equity: Supporting Girls in STEM Without Diminishing Boys.” FIRST, 5 Feb. 2020, www.firstinspires.org/community/inspire/stem-gender-equity. Figure 1. UNSCO Institute of Statistics estimates based on July, 2015

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed